Comics

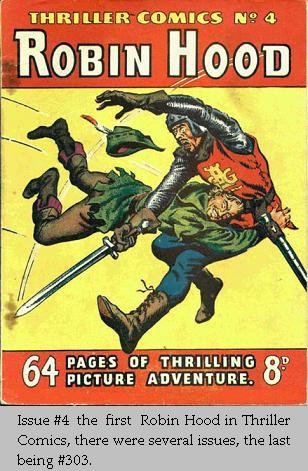

Robin Hood’s first appearance in comics came from Britain:

1920 Robin Hood appeared in a Dreamy Daniel comic strip (drawn by George Davey) in Lot-o’-Fun.

1922 to 1941 In the comic Bubbles in a 20 year run (drawn by Vincent Daniel).

1923 In The Chick’s Own.

1930 In Merry and Bright.

1937 In Sparkler.

The comics of the period still contained serialised fiction: Puck ran a Robin Hood serial in 1912, as did The Rainbow in 1920 and Sunbeam in 1931.

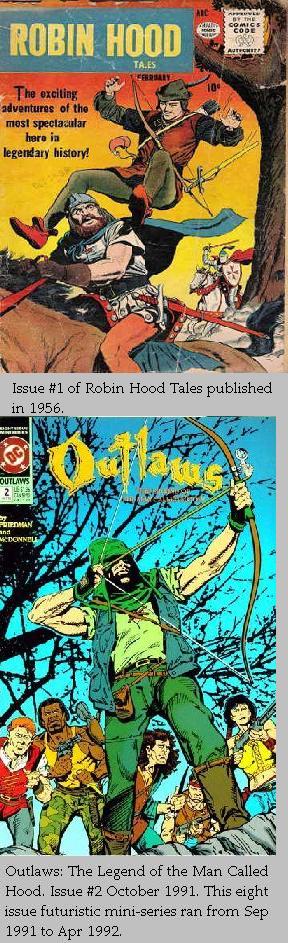

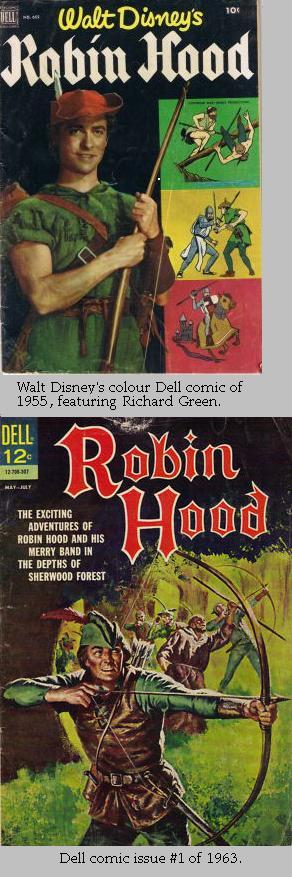

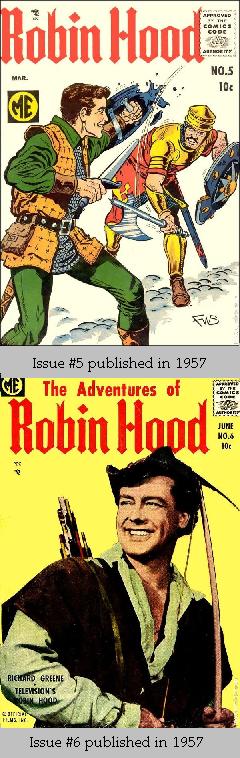

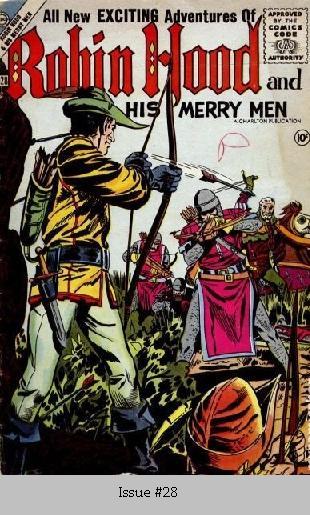

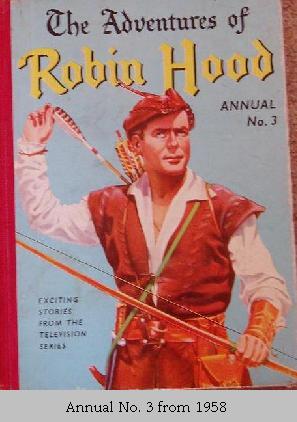

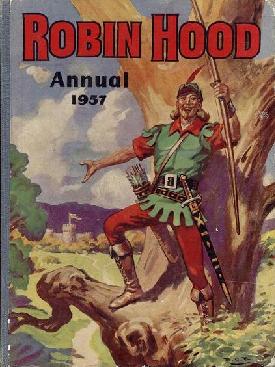

Robin Hood appeared in a number of American comics including DC comics. He first appeared in New Adventure Comics vol. 1 #23 (January 1938). He then shows up in Robin Hood Tales #1 (February 1956) published by Quality Comics; the series was later bought and published by National Comics starting withRobin Hood Tales #7 (Februry 1957). National Comics became a DC Comic. There are a number of comics that include Robin Hood (or a representation of him) which would evolve into or were part of the DC label. Here is a selection of some of them:

| Robin Hood is charactized in issues seven to nine of Green Hornet Comics published by Harvey in 1942. |

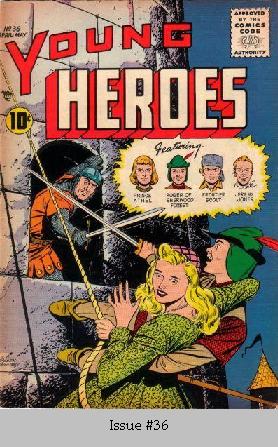

| The little known Roger of Sherwood Forest in the Young Heroes anthology, issues thirty five to thirty seven, published by American Comics Group in the 1950s. |

| Walt Disney Productions ‘The Adventures of Robin Hood’ is a Gold Key Comic series, a seven issue tie-in with the Disney animated movie of 1973, which has animals as the characters.

Issue# 1, March, 1974, The Mystery of Sherwood Forest

Issue# 2, May, 1974, In King Richard’s Service

Issue# 3, July, 1974, The Wizard’s Ring

Issue# 4, August, 1974, The Lucky Hat

Issue# 5, September 1974, The Golden Arrow

Issue# 6, November, 1974, The King’s Ransom

Issue# 7, January 1975, The Bad Baron of Bottomly

|

| Issue one of BBC magazines Robin Hood Adventures (2007), based on the TV series starring Jonas Armstrong, sold in plastic wrapping with free gifts. |

The above section on comics contains information found in comicvine.com; mycomicshop.com; bookpalace.com; comicartfans.com; robinhood-tv.co.uk; ask.com; comicsuk.co.uk; wikipedia.org; boldoutlaw.com; http://fbfiss.blogspot.com/

Interesting Facts about Robin Hood

Robin Hood is first mentioned in print in the late fourteenth-century poem Piers Plowman, which is commonly attributed to William Langland, a contemporary of Geoffrey Chaucer. It was a timely moment for the outlaw to enter literature: English literature as we know it was starting to emerge, and the Peasants’ Revolt – one leader of which, the priest John Ball, even quoted from Langland’s poem – occurred in 1381, shortly after Robin Hood first appeared on the literary scene. It was a time when the social order of England was being challenged and feudalism was rapidly declining.

Why is Doncaster and Sheffield’s airport named after Robin Hood? There are several reasons. First, the earliest stories which mention Robin Hood are set in Yorkshire, not Nottinghamshire. Yes, Robin Hood’s original home was Barnsdale Forest, not Sherwood. What’s more, the majority of the remaining woodland of Sherwood Forest is actually in Yorkshire, not Nottinghamshire. The fifteenth-century ballad A Gest of Robyn Hode has Robin living in Barnsdale rather then Sherwood Forest. (An MP for Nottingham has recently championed an initiative to attract more tourism to the city by using the iconic Robin Hood to promote Nottingham Castle, but really, perhaps Barnsdale Forest should be using Robin to boost tourism!)

The Gest is our source of many of the familiar features of the Robin Hood story, and many of the characters – Little John, Will Scarlet, Much the Miller’s Son – first appeared in this anonymous poem. The BBC/Talkback television series QI has even revealed that Robin Hood’s cloak was scarlet in some of the Robin Hood tales: one nineteenth-century poem, for instance, has Robin in scarlet while his men don the famous Lincoln green.

Nottingham, while we’re at it, derives its name from Snotingaham, the original name for the Saxon settlement that stood on the site of the present city: Snot was the Saxon chieftain who settled there, and somewhere along the way the initial ‘S’ was dropped.

Friar Tuck, the famous man of the cloth among Robin’s merry men, was a real person in fifteenth-century England, whose original name was Robert Stafford. He was a Sussex chaplain who assumed the name ‘Frere Tuk’ around 1417, though whether in honour of the man from the Robin Hood tales we cannot be sure. One thing we can say of Friar Tuck in the Robin Hood stories, though, is that Tuck wasn’t his name: the ‘tuck’ was the belt which Franciscan monks wore round their robes. (This chimes with Robin, whose second name refers to his hood, and Will Scarlet, whose ‘surname’ seems to indicate the colour of the clothing he wore.)

Robin’s king wasn’t the absent crusading Richard the Lionheart (reigned 1189-99) in the original Geststory – the Gest of Robyn Hode refers to ‘King Edward’, not Richard or John, and this puts Robin Hood later in English history, some time after 1272 when Edward I ascended the throne.

The idea of Robin being an outlawed nobleman, Robin of Locksley, derives from Sir Walter Scott’s celebrated medieval romance, Ivanhoe (1820). This novel has also been credited with helping to popularise medieval history for a generation of later writers and artists, among them Tennyson and the Pre-Raphaelites. More recently, Scott’s novel provided the blockbuster 1991 movie starring Kevin Costner,Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, with its source-material for the character of Robin Hood (who is known throughout as ‘Robin of Locksley’; Locksley, by the way, provides us with another Yorkshire connection, since Loxley is the name of a village and suburb of the city of Sheffield in South Yorkshire). Many people criticised Costner for playing Robin with an unashamedly American accent, but Alan Rickman himself appears to have remarked that the American accent was closer to twelfth-century Anglo-Saxon than modern British English (whether this is in fact true, we leave in the hands of the linguists to settle in the comments section below).

Ivanhoe - since we’re mentioning Scott’s novel – was a misspelling of Ivinghoe, a place in Buckinghamshire made famous in a traditional rhyme beginning ‘Tring, Wing and Ivinghoe’. The novel also gave us the name Cedric (Scott supposedly misread a genuine Anglo-Saxon name, Cerdic, and transposed the ‘r’ and ‘d’). Footballer Emile Heskey’s middle name is Ivanhoe – the novel is reputedly his dad’s favourite.

No comments:

Post a Comment